Rifling

Rifling is the process of making spiral grooves in the barrel of a gun or firearm, which imparts a spin to a projectile around its long axis. This spin serves to gyroscopically stabilize the projectile, improving its aerodynamic stability and accuracy.

Rifling is described by its twist rate, which indicates the distance the bullet must travel to complete one full revolution, such as "1 turn in 10 inches" (1:10 inches), or "1 turn in 30 cm" (1:30 cm). A shorter distance indicates a "faster" twist, meaning that for a given velocity the projectile will be rotating at a higher spin rate.

A combination of the weight, length and shape of a projectile determines the twist rate needed to stabilize it – barrels intended for short, large-diameter projectiles like spherical lead balls require a very low twist rate, such as 1 turn in 48 inches (122 cm).[1] Barrels intended for long, small-diameter bullets, such as the ultra-low-drag, 80-grain 0.223 inch bullets (5.2 g, 5.56 mm), use twist rates of 1 turn in 8 inches (20 cm) or faster.[2]

In some cases, rifling will have twist rates that increases down the length of the barrel, called a gain twist or progressive twist; a twist rate that decreases from breech to muzzle is undesirable, as it cannot reliably stabilize the bullet as it travels down the bore.[3][4] Extremely long projectiles such as flechettes may require impractically high twist rates; these projectiles must be inherently stable, and are often fired from a smoothbore barrel.

Contents |

History

Muskets were smoothbore, large caliber weapons using ball-shaped ammunition fired at relatively low velocity. Due to the high cost and great difficulty of precision manufacturing, and the need to load readily from the muzzle, the musket ball was a loose fit in the barrel. Consequently on firing the ball bounced off the sides of the barrel when fired and the final direction on leaving the muzzle was unpredictable.

Barrel rifling was invented in Augsburg at the end of the fifteenth century.[5] In 1520 August Kotter, an armourer of Nuremberg, improved upon this work. Though true rifling dates from the mid-16th century, it did not become commonplace until the nineteenth century.

Recent developments

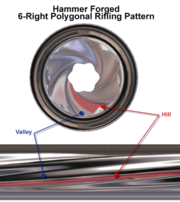

Polygonal rifling

The grooves most commonly used in modern rifling have fairly sharp edges. More recently, polygonal rifling, a throwback to the earliest types of rifling, has become popular, especially in handguns. Polygonal barrels tend to have longer service lives because the reduction of the sharp edges of the land reduces erosion of the barrel. Supporters of polygonal rifling also claim higher velocities and greater accuracy. Polygonal rifling is currently seen on pistols from Heckler & Koch, Glock and Kahr Arms, as well as the Desert Eagle.

Extended range, full bore concept

For tanks and artillery pieces, the extended range, full bore concept developed by Gerald Bull for the GC-45 howitzer reverses the normal rifling idea by using a shell with small fins that ride in the grooves, as opposed to using a slightly oversized projectile which is forced into the grooves. Such guns have achieved significant increases in muzzle velocity and range. Examples include the South African G5 and the German PzH 2000.

Manufacture

Most rifling is created by either:

- cutting one groove at a time with a machine tool (cut rifling or single point cut rifling);

- cutting all grooves in one pass with a special progressive broaching bit (broached rifling);

- pressing all grooves at once with a tool called a "button" that is pushed or pulled down the barrel (button rifling);

- forging the barrel over a mandrel containing a reverse image of the rifling, and often the chamber as well (hammer forging);

- flow forming the barrel preform over a mandrel containing a reverse image of the rifling (rifling by flow forming)[6]

The grooves are the spaces that are cut out, and the resulting ridges are called lands. These lands and grooves can vary in number, depth, shape, direction of twist (right or left), and twist rate (see below). The spin imparted by rifling significantly improves the stability of the projectile, improving both range and accuracy. Typically rifling is a constant rate down the barrel, usually measured by the length of travel required to produce a single turn. Occasionally firearms are encountered with a gain twist, where the rate of spin increases from chamber to muzzle. While intentional gain twists are rare, due to manufacturing variance, a slight gain twist is in fact fairly common. Since a reduction in twist rate is very detrimental to accuracy, gunsmiths who are machining a new barrel from a rifled blank will often measure the twist carefully so they may put the faster rate, no matter how minute the difference is, at the muzzle end (see internal ballistics for more information on accuracy and bore characteristics).

Construction and operation

A barrel of circular cross-section is not capable of imparting a spin to a projectile, so a rifled barrel has a non-circular cross-section. Typically the rifled barrel contains one or more grooves that run down its length, giving it a cross-section resembling a gear, though it can also take the shape of a polygon, usually with rounded corners. Since the barrel is not circular in cross-section, it cannot be accurately described with a single diameter. Rifled bores may be described by the bore diameter (the diameter across the lands or high points in the rifling), or by groove diameter (the diameter across the grooves or low points in the rifling). Differences in naming conventions for cartridges can cause confusion; for example, the .303 British is actually slightly larger in diameter than the .308 Winchester, because the ".303" refers to the bore diameter in inches, while the ".308" refers to the groove diameter in inches (7.70 mm and 7.82 mm, respectively).

Despite differences in form, the common goal of rifling is to deliver the projectile accurately to the target. In addition to imparting the spin to the bullet, the barrel must hold the projectile securely and concentrically as it travels down the barrel. This requires that the rifling meet a number of tasks:[4]

- It must be sized so that the projectile will swage or obturate upon firing to fill the bore.

- The diameter should be consistent, and must not increase towards the muzzle.

- The rifling should be consistent down the length of the bore, without changes in cross-section, such as variations in groove width or spacing.

- It should be smooth, with no scratches lying perpendicular to the bore, so it does not abrade material from the projectile.

- The chamber and crown must smoothly transition the projectile into and out of the rifling.

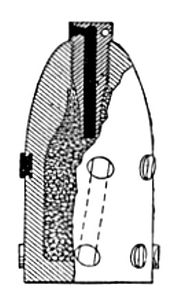

When the projectile is swaged into the rifling, it takes on a mirror image of the rifling, as the lands push into the projectile in a process called engraving. Engraving takes on not only the major features of the bore, such as the lands and grooves, but also minor features, like scratches and tool marks. The relationship between the bore characteristics and the engraving on the projectile are often used in forensic ballistics.

Fitting the projectile to the bore

The original firearms were loaded from the muzzle by forcing a ball from the muzzle to the breech. Whether using a rifled or smooth bore, a good fit was needed to seal the bore and provide the best possible accuracy from the gun. To ease the force required to load the projectile, these early guns used an undersized ball, and a patch made of cloth, paper, or leather to fill the windage (the gap between the ball and the walls of the bore). The patch provided some degree of sealing, kept the ball seated on the charge of black powder, and kept the ball concentric to the bore. In rifled barrels, the patch also provided a means to transfer the spin from the rifling to the bullet, as the patch is engraved rather than the ball. Until the advent of the hollow-base Minié ball, which obturates upon firing to seal the bore and engage the rifling, the patch provided the best means of getting the projectile to engage the rifling.[7]

In breech-loading firearms, the task of seating the projectile into the rifling is handled by the throat of the chamber. Next is the freebore, which is the portion of the throat down which the projectile travels before the rifling starts. The last section of the throat is the throat angle, where the throat transitions into the rifled barrel.

The throat is usually sized slightly larger than the projectile, so the loaded cartridge can be inserted and removed easily, but the throat should be as close as practical to the groove diameter of the barrel. Upon firing, the projectile expands under the pressure from the chamber, and obturates to fit the throat. The bullet then travels down the throat and engages the rifling, where it is engraved, and begins to spin. Engraving the projectile requires a significant amount of force, and in some firearms there is a significant amount of freebore, which helps keep chamber pressures low by allowing the propellant gases to expand before being required to engrave the projectile. Best accuracy, however, is typically provided with a minimum of freebore, maximizing the chances that the projectile will enter the rifling without distortion.[8][9]

Twist rate

For best performance, the barrel should have a twist rate sufficient to stabilize any bullet that it would reasonably be expected to fire, but not significantly more. Large diameter bullets provide more stability, as the larger radius provides more gyroscopic inertia, while long bullets are harder to stabilize, as they tend to be very backheavy and the aerodynamic pressures have a longer "lever" to act on. The slowest twist rates are found in muzzleloading firearms meant to fire a round ball; these will have twist rates as low as 1 in 60 inches (1,500 mm), or slightly longer, although for a typical multi-purpose muzzleloader rifle, a twist rate of 1 in 48 inches (1,200 mm) is very common. The M16A2 rifle, which is designed to fire the SS109 bullet, has a 1 in 7-inch (180 mm) twist. Civilian AR-15 rifles are commonly found with 1 in 12 inches (300 mm) for older rifles and 1 in 9 inches (230 mm) for most newer rifles, although some are made with 1 in 7 inches (180 mm) twist rates, the same as used for the M16. Rifles, which generally fire longer, smaller diameter bullets, will in general have higher twist rates than handguns, which fire shorter, larger diameter bullets.

In 1879, George Greenhill, a professor of mathematics at the Royal Military Academy (RMA) at Woolwich, London, UK[10] developed a rule of thumb for calculating the optimal twist rate for lead-core bullets. This shortcut uses the bullet's length, needing no allowances for weight or nose shape[11]. The eponymous Greenhill Formula, still used today, is:

where:

- C = 150 (use 180 for muzzle velocities higher than 2,800 f/s)

- D = bullet's diameter in inches

- L = bullet's length in inches

- SG = bullet's specific gravity (10.9 for lead-core bullets, which cancels out the second half of the equation)

The original value of C was 150, which yields a twist rate in inches per turn, when given the diameter D and the length L of the bullet in inches. This works to velocities of about 840 m/s (2800 ft/s); above those velocities, a C of 180 should be used. For instance, with a velocity of 600 m/s (2000 ft/s), a diameter of 0.5 inches (13 mm) and a length of 1.5 inches (38 mm), the Greenhill formula would give a value of 25, which means 1 turn in 25 inches (640 mm).

Improved formulas for determining stability and twist rates include the Miller Twist Rule[12] and the McGyro program[13] developed by Bill Davis and Robert McCoy.

If an insufficient twist rate is used, the bullet will begin to yaw and then tumble; this is usually seen as "keyholing", where bullets leave elongated holes in the target as they strike at an angle. Once the bullet starts to yaw, any hope of accuracy is lost, as the bullet will begin to veer off in random directions as it precesses.

Conversely, too-high a rate of twist can also cause problems. The excessive twist can cause accelerated barrel wear, and also induce a very high spin rate which can cause high-velocity projectiles to disintegrate in flight. A higher twist than needed can also cause more subtle problems with accuracy: Any inconsistency within the bullet, such as a void that causes an unequal distribution of mass, may be magnified by the spin. Undersized bullets also have problems, as they may not enter the rifling exactly concentric and coaxial to the bore, and excess twist will exacerbate the accuracy problems this causes. Lastly, excessive spinning causes a reduction in the lateral kinetic energy of a projectile, thereby reducing its destructive power (the energy instead becomes rotational kinetic energy).

Bullet revolutions per minute (rpm)

A bullet fired from a rifled barrel can spin at over 300,000 rpm, depending on the bullet's muzzle velocity (MV) and the barrel's twist rate.

The general formula for calculating the rpm of a rotating object may be written as

where  is the linear velocity of a point in the rotating object (in units of distance/minute) and C refers to the circumference of the circle that this measuring point performs around the axis of rotation.

is the linear velocity of a point in the rotating object (in units of distance/minute) and C refers to the circumference of the circle that this measuring point performs around the axis of rotation.

For a bullet, the specific formula below uses the bullet's MV and the barrel's twist rate to calculate rotational speed:

- MV(in fps) x (12/twist rate in inches) x 60 = Bullet rpm

For example, a bullet with a muzzle velocity of 3050 ft/s fired from a barrel with a twist rate of 1 in 7-inch (180 mm) (e.g., the M16A2 rifle) spins at ~315,000 rpm[14].

Excessive rotational speed can exceed the bullet's designed limits and the resulting centrifugal force can cause the bullet to disintegrate in a radial fashion[15].

See also

- Rifle

- Smoothbore

- Paradox gun

- Comparison microscope

- Gun barrel sequence (James Bond)

References

- ↑ Randy D. Smith. "The .54 Caliber Muzzleloader". Chuck Hawks. http://www.chuckhawks.com/54_caliber_muzzleloader.htm.

- ↑ "Products::Rifle Barrels::Calibers and Twists". Shilen Rifles, Inc.. http://www.shilen.com/calibersAndTwists.html.

- ↑ "gain twist". MidwayUSA GunTec Dictionary. http://www.midwayusa.com/guntecdictionary.exe/showterm?TermID=2535.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Dan Lilja. "What makes a barrel accurate?". http://riflebarrels.com/articles/barrel_making/rifle_barrel_accurate.htm.

- ↑ W. S. Curtis. "Long Range Shooting: A Historical Perspective". http://www.lrml.org/historical/longrange/history02.htm.

- ↑ BARIŞ GÜN and ILHAN GÜVEL. Rifling By Flow Forming.

- ↑ Sam Fadala (2006). The Complete Blackpowder Handbook: The Latest Guns and Gear. Gun Digest. ISBN 0896893901. Chapter 18, The Cloth Patch

- ↑ P. O. Ackley (1966). Handbook for Shooters & Reloaders Volume II. Plaza Publishing. pages 97-98

- ↑ Daniel Lilja. "Thoughts on Throats for the 50 BMG". http://www.riflebarrels.com/articles/50calibre/throats_50_bmg.htm.

- ↑ School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland. Alfred George Greenhill (October 2003) .http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/~history/Biographies/Greenhill.html

- ↑ Mosdell, Matthew. The Greenhill Formula.http://www.mamut.net/MarkBrooks/newsdet35.htm (Accessed 2009 AUG 19)

- ↑ Miller, Don. How Good Are Simple Rules For Estimating Rifling Twist, Precision Shooting - June 2009

- ↑ http://www.jbmballistics.com/downloads/text/mcgyro.txt

- ↑ [1] Calculating Bullet RPM

- ↑ [2] Twist Rate

External links

- Article on barrel making from an IHMSA shooter

- Rifling By Flow Forming A new developed method for rifling.

- Article on barrel making from Lilja, a maker of world class competition barrels

- Article on making and measuring rifling by Lilja; includes pictures of button rifling machine

- 6mmBR article on barrels

- Bore slugging tutorial, explaining now to determine the true bore and groove size and choose appropriate bullet diameters

- Calculating Bullet RPM — Spin Rates And Stability